The Nambu Toji of Iwate

I’ve always loved sake, however, I’ve always been blissfully ignorant of the nuances, history, and craftsmanship of the liquor. Though there are many sake producing regions, also known as Toji Guilds, the three most famous are the Tanba Toji of Hyogo Prefecture, the Echigo Toji of Niigata Prefecture and the Nambu Toji of Iwate Prefecture. In total there are currently over 30 Toji Guilds in Japan.

The title of toji refers to the Master Brewer of a sake brewery. The toji is responsible for every aspect of the brewing process, starting with determining what type of sake rice is purchased and on through every step thereafter. There is only ever one toji at each brewery. Historically, the toji and kuramoto (Brewery Owner) were always two separate individuals; however, over time these roles have sometimes been combined.

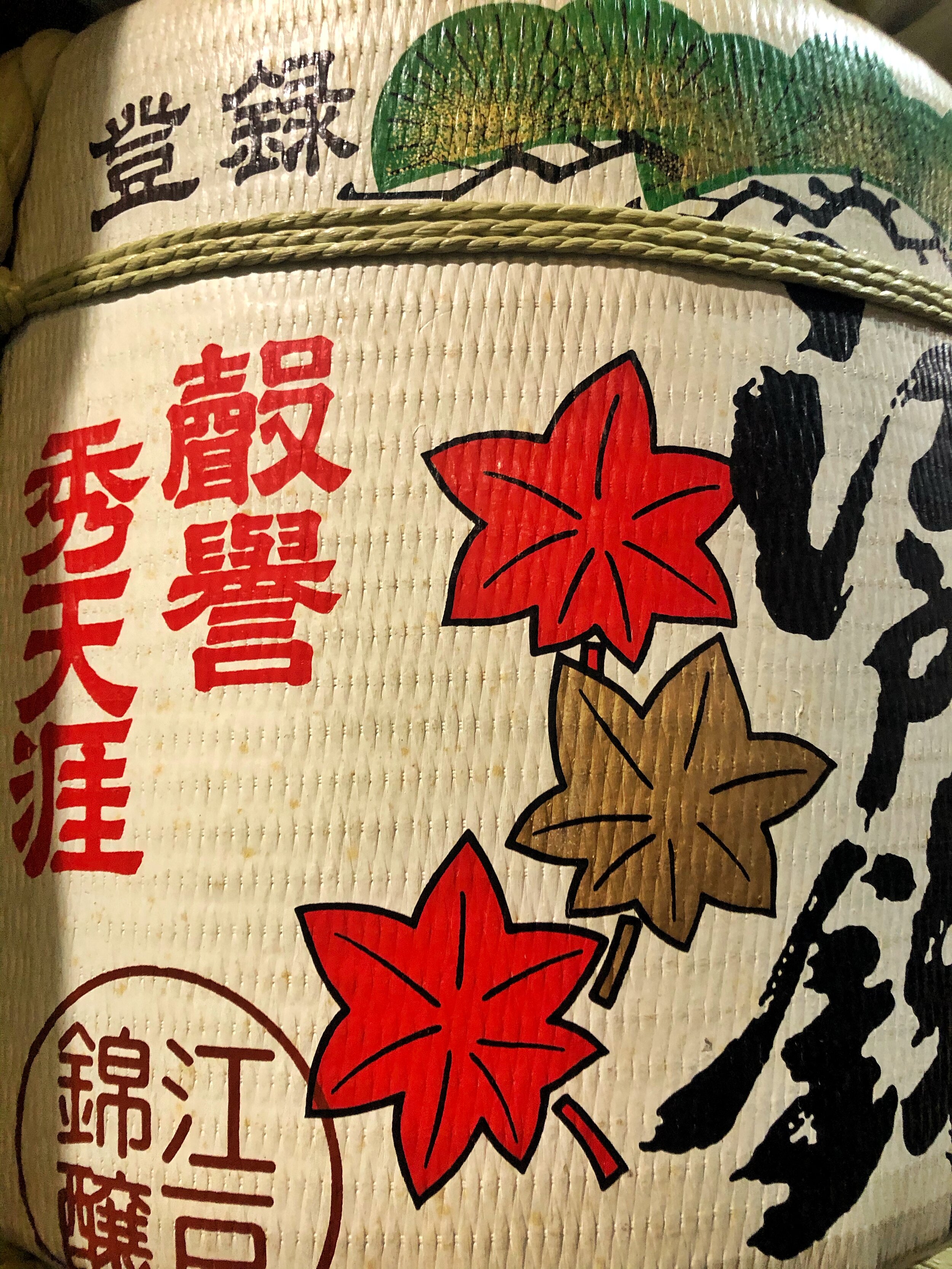

The Nambu Toji has roughly 400 toji under them and is one of the largest Toji Guilds in Japan. Whilst in Hanamaki, I visited the Nambu Toji Museum and was astounded to realise how widely dispersed their toji are. It is mindblowing to realise that so many sake breweries in Japan have roots in the brewing techniques of the Nambu. The above left photo showcases just a small range of the many sake that have been brewed by Nambu Toji around Japan. In fact, it was an entire wall of the museum. I forgot to take a photo of it, but there’s a map of Japan in the museum which showcases where the Nambu Toji have dispersed all over the country.

SUGIDAMA

A sugidama is a large ball comprised of balled up cedar branches. Originally green when made, when the sugidama turns fully brown, it means that the good sake is nearly ready! They are traditionally hung from the outdoor awnings of breweries.

THE 4 TYPES OF SAKE

I’ve always enjoyed sake, but I am no connoisseur. It took me this trip to Iwate to learn that there were 4 popular types: Junmai, Honjozo, Ginjo and Daiginjo. Previously, I would make my choice simply whether a sake was sweet or dry. The difference between the types is the percentage (ratio) of the rice grain remaining after being polished during the process, and how much alcohol (if any) has been added. This is known as the polishing ratio. The rice polishing ratio is an important component of making sake as it’s a critical factor in how sake is categorised and priced.

Daiginjos are considered the highest quality of sake with a minimum 50% polishing ratio and a small amount of distilled alcohol, followed by Ginjo which are polished at minimum 40%. These two are fairly similar to each other.

Honjozo are polished to a minimum of 70% and hold a light, mildly fragrant taste. They also have a small amount of distilled alcohol added to them.

Junmai is the only type of sake with no minimum polishing ration and no alcohol has been introduced. If you ever have a sake that is considered a Daiginjo-junmai or Ginjo-junmai, that means no alcohol has been added to these combinations.

THE SAKE OUTLAW OF JAPAN

My favourite aspect of travelling is finding those little unknown gems, whether it be a destination, a hidden location, an individual’s story, just something that really connects you to a place. I was lucky on this trip to hear the tale of Naotaka Kawamura. Told to me by local guide, translator, lover of sake and his friend Quinlan, Kawamura-san is the kuramoto and toji of the last sake brewery of Ishidoriya; Kawamura Shuzo (founded 1922)

A self proclaimed “sake outlaw”, Kawamura-san embarked on a sake pilgrimage over 20 years ago, travelling extensively throughout Japan visiting other breweries and toji, learning their stories and what inspired them. When he returned, Yoemon was created, a new brand of sake named after his grandfather, the founder of Kawamura Shuzo. The brand Yoemon and it’s other sister brands, are revered amongst those who are true sake connoisseurs. It was a realisation that was further reinforced a couple weeks later when I was in Shizuoka one night at a tiny soba restaurant; the chef (a lover of sake) was duly impressed and awed all at once that this Australian girl had heard about Yoemon and Kawamura Shuzo, and then we proceeded to drink delicious sake from his collection together! hahaha I do love those moments in Japan.

I was also doubly thrilled when at perhaps my utmost current favourite sushi, sake & wine pairing omakase restaurant, the sake sommelier was delighted to learn that I knew about Kawamura Shuzo and brought out a rare bottle for us to have a drink (initially it wasn’t included with our pairings).

One of the elements I love about Japan is its artisan ethic, its purity in honing something to the best it can be and doing it on one’s own terms. Kawamura Shuzo has no social media presence at all, it is only sold at it’s brewery in Iwate, one single liquor shop on the outskirts of town (where I was able to buy the sake bottle with the red label) and a few select restaurants around Japan. When the sommelier told me his experience trying to purchase Kawamura Shuzo Yoemon, it further reinforced how particular Kawamura-san was about who is allowed to stock his product. It is entirely dependent if Kawamura-san himself feels a kinship with those people and their establishments.

Unfortunately I was unable to visit the brewery itself, as it is closed on Mondays, but I hope to return in the future to finally visit, meet and hopefully have a couple of drinks with the elusive Kawamura-san.